If you’re confused by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s reporting requirements for COVID-19 cases, you’re not alone. It has become a moving target since the pandemic hit the U.S. earlier this year. We talked to leading experts in the field to help shed some clarity on the question.

Even as employers do all they can to decrease the spread of COVID-19 inside their facilities and reduce its potential impact on their employees, it’s still unfortunately likely that some will contract the coronavirus.

So inevitably the question will arise as to whether the illness is work-related and therefore recordable (or reportable) under the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recordkeeping standards.

If the rules for reporting perplex you, you’re not alone. Many employers have reported being confused about their responsibilities.

To shed more clarity on the question, we spoke with three experts in this field: Eric J. Conn of Conn Maciel Carey LLP, chair of the company’s Workplace Safety Group; Rick Warren, labor and employment partner at FordHarrison LLP; and Courtney Malveaux, principal at Jackson Lewis P.C. Specifically, we asked them to describe the current requirements for employers, to detail any important recent changes, and to suggest best practices for companies trying to deal with the reporting requirements.

How Did We Get Here?

In its first guidance on the question, issued on April 10, OSHA recognized the difficulty of determining whether a COVID-19 case is “work-related” due to potential employee infections at home, in the community or elsewhere. Realizing that employers needed to focus on workplace protective measures such as disinfecting worksites and implementing other safety measures, OSHA limited the reporting requirements to employers in certain high-risk industries, such as healthcare, first responders or correctional institutions. Most employers were therefore exempt from making work-related determinations.

On May 19, OSHA updated its guidance, stating that COVID-19 illnesses “are likely work-related when several cases develop among workers who work closely together and there is no alternative explanation.” Two months later, OSHA provided additional guidance on reporting COVID-19 hospitalizations, but the agency rescinded that guidance two weeks later.

OSHA’s changing guidance has been confusing for employers, says Conn Maciel Carey LLP’s Eric J. Conn, and many have pushed for COVID-19 to be folded into OSHA’s exemption for the common cold and flu when it comes to recordkeeping and reporting. The agency clearly didn’t believe they could do that lawfully, he adds: “The reason is, COVID-19 is not the cold or flu; epidemiologically it’s a different virus, so OSHA can’t just wave a magic wand and say, ‘This is just like the cold or flu, and therefore it’s exempt.’”

Read more: Tackling the Manufacturing Skills Gap: 5 Skills Your Company Will Need Soon

In fact, in its guidance documents issued in April and May, OSHA has basically “doubled-down” on its decision that employers should focus their efforts on determining whether cases of COVID-19 are work-related, he says.

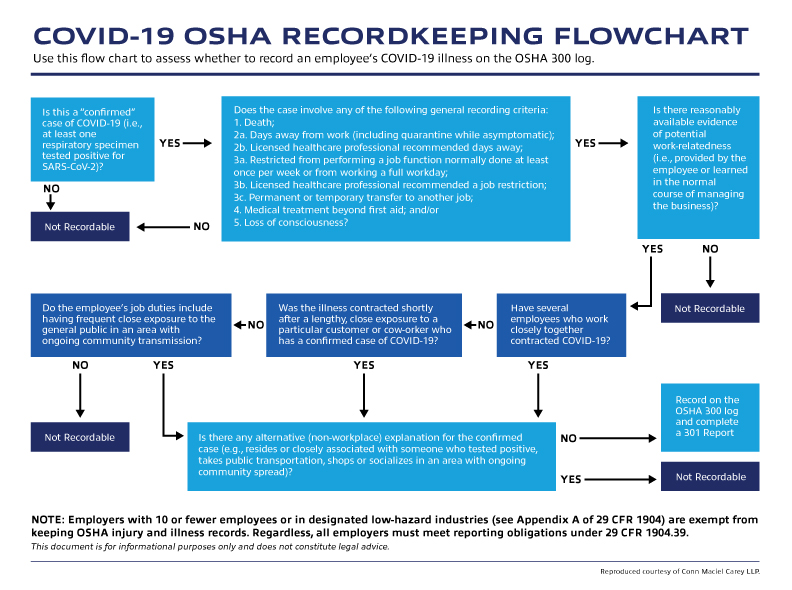

Thankfully, as Conn and his colleagues note in a blog post, one consistent aspect of all of OSHA’s COVID-19 guidance has been “the basic structure for evaluating whether an employee’s COVID-19 case is recordable.” According to the post, the criteria that make a case of COVID-19 recordable by employers are:

The case of COVID-19 is a confirmed case.

The case involves one or more of the general recording criteria in 29 CFR 1904.7 (medical treatment beyond first aid; days away from work; etc.)

The case is work-related, as defined in 29 CFR 1904.5.

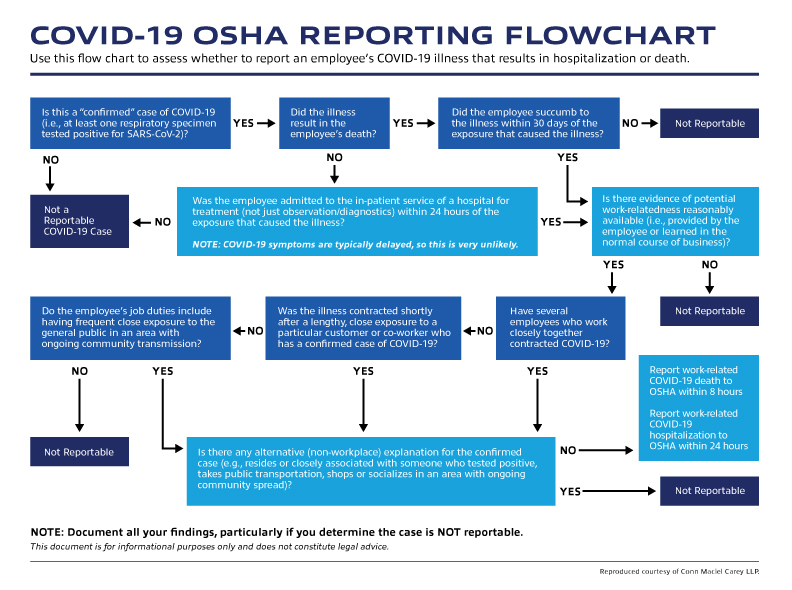

Whether cases are reportable is another matter. These are cases when recording the incident on the 300 log is no longer enough—employers must actually pick up the phone and call OSHA.

To determine whether to report a COVID-19 illness to OSHA, employers must conclude whether the case is confirmed and whether it is work-related. If those criteria are met there are other OSHA requirements that employers must examine. See the flowcharts below to help you visualize whether an employee’s COVID-19 case should be considered recordable or reportable.

“The biggest issue in all of this, in my mind, is how to determine whether something is work-related, and the guidance OSHA offered about the existence of any alternative, non-work explanation for the illness undermining work-relatedness even in the face of a demonstrable work-related exposure,” says Conn.

The examples that OSHA gives of circumstances that are likely work-related are clear exposures that occur in the workplace “and there is no alternative explanation,” he adds. “What that means to me is that if there are two identifiable exposures—one at work and one away from work—OSHA’s guidance forces a conclusion that the case is not work-related. That’s where the rubber meets the road, and why I have recommended that so few cases need to be recorded or reported.”

What Are Some Best Practices for Employers?

Employers naturally want to avoid censure, but overreporting workplace illnesses and injuries is a common trap for employers because it can lead to a raft of unintended consequences, says Courtney Malveaux of Jackson Lewis P.C. It potentially exposes a company to closer scrutiny from OSHA and citations that you have to defend, and it can drive up your injury rates in a way that puts your company at a competitive disadvantage, he says.

“Many safety professionals will overrecord and overreport and generally err on the side of caution so they don’t get a violation—that’s how they’re trained,” Malveaux says. It’s not wrong to do so, he continues, but “from a business standpoint I urge caution because I have had clients who have overrecorded and lost business opportunities because they had more entries in their OSHA 300 logs.”

“If you’re doing your diligence and you’re able to justify everything in writing, it’s very important to do that,” he adds. “OSHA is throwing the ball back into the lap of manufacturers and other employers, so they have to make these determinations on their own.”

The potential negative consequences of overreporting include:

A company may do sustainability assessments before doing business with you, and its due diligence could include things like environmental sustainability, diversity and workplace safety, so it could recoil if it sees a bunch of issues.

Unions may obtain this information and use it as leverage during labor negotiations, and it could be used against a company by disgruntled employees, leading to negative publicity and reputational damage.

If you are underrecording or underreporting, or seeming to turn a blind eye to cases, and OSHA investigates, then the agency could take a more aggressive posture toward your company.

Read more: Virtual Safety Training: How MSA Uses Technology to Safeguard Your Workers

Malveaux advises documenting as much as you can and doing as much of the intelligence gathering as you can in case OSHA comes knocking.

He also suggests that companies check for rules in their home states. The Virginia Safety and Health Codes Board, for example, which is the board that enacts OSHA standards in the state, has passed a standard requiring employers in the state to control, prevent and mitigate the spread of the virus in the state, and the standard applies to most of the state’s private employers and state and local employees.

“Virginia is just one example, so manufacturers should be aware of whether there are state-specific standards relating to recording and reporting,” Malveaux says.

What’s Coming Next That Manufacturing Companies Should Know About?

The possibility of a “twindemic”—two epidemics at the same time—is likely to make COVID-19 reporting more challenging for businesses. Cold and flu season is set to start in October in the Northern Hemisphere, and when combined with the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation is “going to be even more of a muddled mess in the fall and winter,” warns Eric Conn.

The milder cases of COVID-19 look a lot like the seasonal flu, so we are going to have a lot of challenging determinations about whether an illness is COVID-19 or the flu, Conn says.

“We’ll have lots of employees missing work because they’re perhaps being extra cautious when they have flu or cold symptoms, so there’s going to be a lot more cases to evaluate for potential recordability, and it’s going to continue to be a huge burden on employers, which by the way is the reason why so many of us were pushing to have them exempt COVID-19 cases from record-keeping,” he says. “It’s not to hide anything, it’s because it’s a waste of time and resources when it’s not a uniquely workplace-related issue and it’s consuming an extraordinary amount of time to little or no benefit.”

Rick Warren, labor and employment partner at FordHarrison LLP, notes that the first wave of citations and penalties for coronavirus-related illnesses are beginning to surface. OSHA has six months to issue a citation, so cases that came to light in March and April at the start of the pandemic are now appearing.

Read more: Coronavirus and Workplace Safety: How to Manage Employees During a Pandemic

“OSHA has started issuing citations for failing to protect employees, or failing to adhere to general standards,” Warren says. Though OSHA has only issued various guidance and no standard, it is focused on a catchall: the general duty clause, which requires employers to provide each worker in their place of employment protection from recognized hazards that are likely to cause physical harm.

This is why companies should be able to demonstrate, to the extent that they can, their plan to protect their employees, Warren says.

“On an assembly line, for example, are you requiring social distancing or wearing of masks? Have you arranged for frequent deep cleaning to be done? These are the things you can do to minimize the likelihood that someone who gets the virus outside of work can bring it to work with them. OSHA will ask what measures you have taken, and if you haven’t taken them it can say you have violated the general-duty clause.”

OSHA recently published frequently asked questions and answers (FAQs) regarding the need to report employees’ in-patient hospitalizations and fatalities resulting from work-related cases of the coronavirus.

How are you handling OSHA recording and reporting rules for COVID-19 cases? What best practices have you established? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Why You Need a COVID-19 Response Plan

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as the old saying goes, and for small-to-medium-sized companies trying to mitigate the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s vital to formulate a written infection control and response plan, says Eric J. Conn of Conn Maciel Carey LLP and chair of OSHA’s Workplace Safety Group.

“It’s the most important thing every employer can and should be doing right now if they haven’t already,” Conn says. “You should have a plan in place both for how to deal with potential exposures, and outlining the workplace safety controls that you have probably already implemented but maybe you haven’t memorialized in one written plan.”

The plan should identify how you’re going to ensure social distancing, how you’re going to avoid congestion in common areas of the workplace and lots of close contact interactions, and what you’re going to do in the way of enhanced cleaning to mitigate those exposures.

You also need to have a plan for what you’re going to do when you have a positive case in your workplace, Conn continues.

“Part of that plan is identifying what potential exposures occurred in the workplace so you can communicate to your workers that one of their co-workers has become ill with COVID-19, and that they ought to see a doctor and get tested.”

Next is doing an assessment of potential work-relatedness, he adds.

“Look at the employee that has tested positive,” Conn says. “What are his or her job responsibilities? Where in the facility does he or she work? Are there other co-workers that by necessity he or she has close interactions with? Are they sharing tools or machines? Are they working in the same vicinity as each other?”

These questions help you identify whether there are other exposures at work that may have caused this illness, and then you do, to the extent you can, some level of work-relatedness questionnaire, whether you’re asking the employee who has contracted the illness, or his or her co-workers or family members, to try to identify what’s happening outside the workplace that may have contributed to this illness.

“So, for example, if you have three guys on the same line who take their breaks together, or share tools, and they’ve all tested positive within a week of each other, that looks like it’s work-related,” Conn says. “I can then do a little bit of an assessment and learn that all three of them play on a softball team together, or all three did a bunch of social activities together in a community where there’s active community spread, and I can then conclude that a case that might look work-related has a different cause.”

“You can make it as simple as four or five questions,” he adds. Conn Maciel Carey LLP has published a suggested work-relatedness questionnaire template on its site that employers can use as a guide to determine whether there is an alternative explanation for an employee’s infection.

Related Articles

Worthy Waterproof Gloves You'll Want to Wear

![Why the Cheapest Safety Gloves Aren’t Always the Smartest [Infographic]](https://images.ctfassets.net/5j4ln2up7bt7/2gVEyRZylkBIlvTDtTRRc7/dde0c00e4846d6a88d56a7a68f09332a/mcr-PD5931_action4571-thumb.jpg)

Why the Cheapest Safety Gloves Aren’t Always the Smartest [Infographic]

NFPA 30 and Safe Storage of Flammable Liquids

Why Mental Health Belongs in Every Safety Conversation