Shifting Trade War Winds: Tariffs Remain Top of Mind

Here’s a closer look at the economic effects of a lingering trade war with tariffs.

Here’s a closer look at the economic effects of a lingering trade war with tariffs.

What’s the latest news on tariffs? It remains a mixed bag of uncertainty. We talk to manufacturing industry advocates and analysts—and take the pulse on how it is affecting the aerospace and automotive industries.

Overall, U.S. manufacturing remained healthy in early 2019.

After a softening of demand in Q4 2018, activity picked up in January but then softened slightly at the end of February, says Omar S. Nashashibi, founding partner of The Franklin Partnership LLP and head of government relations for One Voice, the advocacy program of the Precision Metalforming Association and the National Tooling and Machining Association.

As of early March, automotive was flat and aerospace was rising.

“Aerospace seems to continue to do well with increases expected,” says Nashashibi, fresh from several industry conferences. “Most of the people in aerospace and defense with whom I spoke are very busy.”

Yet slower growth in China combined with the trade war is creating headwinds, says Jason Alexander, principal and industrial products senior analyst at RSM US LLP.

In January, China lowered its economic growth target for 2019 to a range between 6.0 and 6.5 percent, compared with last year’s 6.5 percent.

It may seem like a subtle shift, but it is significant. If growth is 6.2 percent or lower, “that would be the slowest rate of economic growth in almost three decades in China,” Alexander notes.

On top of that, a constantly shifting mix of tariffs and unilateral negotiations has created a “lingering uncertainty tax” on the industry, he noted.

Tariff concerns, however, did not slow manufacturers from hiring last year: Companies posted net job gains of 284,000 which were the best since 1997—and up about 77,000 from 2017.

As of early March, there were several major fronts in the trade war, all in a state of flux.

Worried about tariffs? Learn how to future your business from tariff fallout.

Last year, the Trump administration placed tariffs ranging from 10 to 25 percent on a host of Chinese goods, including heavy machinery. The 10 percent tariffs were set to rise to 25 percent on March 1, but the administration delayed that increase indefinitely, citing progress in trade talks with China.

Right now, there are reports that the two countries are discussing a potential summit meeting in late April. Another recent report from China said the countries are pushing back meeting until June.

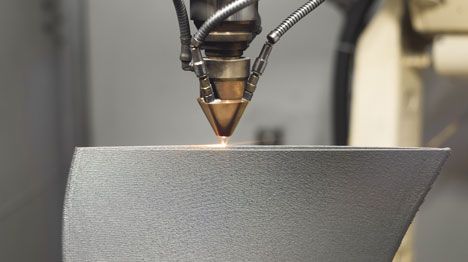

Tariffs are already dampening capital investment by U.S. manufacturers.

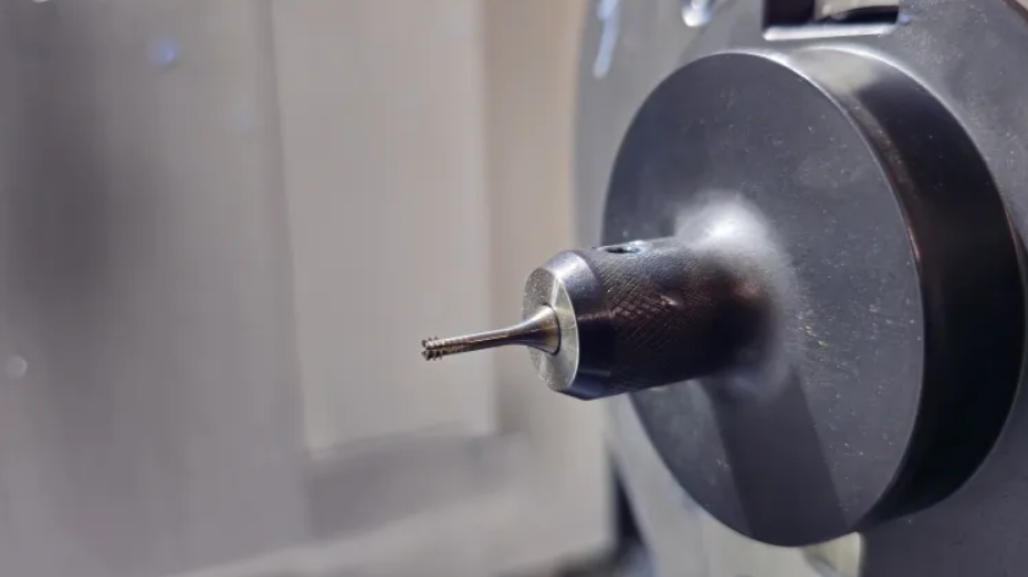

“If you’re bringing in a multimillion-dollar piece of machinery, a 10 percent tariff is very significant. A 25 percent tariff can shut you down,” says Nashashibi. He’s been fielding calls from bankers concerned about loans for capital equipment that could suddenly balloon in cost.

Also, China has imposed retaliatory tariffs on some goods it buys from the U.S., including medical devices and agricultural products, so Chinese buyers are looking for new sources for these goods, he says.

Even things like agricultural products can impact the U.S. manufacturing industry. If farmers can’t sell soybeans, they don’t buy farm equipment, and if they don’t buy farm equipment, the U.S. makers of that equipment (and their suppliers) suffer, notes Nashashibi.

“Increasingly we are seeing manufacturers look not just at the impact of the tariffs on themselves but also throughout their customers’ supply chains upstream,” he says.

Observers had predicted that U.S. companies would take advantage of the provisions of the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to invest in capital equipment, but the trade situation is creating hesitation.

“We are not seeing the boost in capital expenditures that we thought would happen because of tax cut,” says Alexander. “I think it’s because of the continued uncertainty—and also because of the increase in interest rates.”

Also last year, the Trump administration imposed a 25 percent tariff on steel and 10 percent tariff on aluminum imported from most foreign countries, including China, the EU, Canada and Mexico.

There is no official end date for these tariffs, Nashashibi says. The U.S. government’s strategy has been to conduct unilateral negotiations with each country.

“It seems to be the way the president wants to do this,” he says. “If your country signs a trade agreement with the U.S., then we’ll lift the tariffs.”

That approach is playing out with the “new NAFTA” – formally named the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) – which is in limbo.

The agreement, signed last fall by the leaders of the U.S., Canada and Mexico, would require cars and trucks to have a higher percentage of North American materials and components, among other things.

USMCA requires ratification by the legislatures of the three countries, but the chance of that happening soon, or at all, is fading, especially as both the U.S. and Canada enter election seasons. Not to mention a major sticking point: Canada and Mexico want the Section 232 tariffs removed before they ratify the agreement; Trump wants ratification before lifting the tariffs.

Next up could be tariffs on imported automobiles and automotive parts. In February, the Commerce Department sent a confidential report to the White House about the possibility of imposing additional 232 tariffs on automobiles and auto parts. These actions are aimed primarily at the EU and Japan, which supply many automotive imports to the U.S., says Alexander.

“I think that could be an even bigger threat to U.S. manufacturing than what’s going on with China,” he says.

Because the automotive industry makes up some 3 to 3.5 percent of U.S. GDP, such tariffs would ripple through the U.S. economy. Tariffs on imports of auto parts would likely hurt U.S. makers of auto parts, says Michael Robinet, executive director of the automotive global advisory practice at IHS Markit.

How? Here’s an example: U.S.-made alternators may go into imported automobiles, or at least into automobiles that have many imported parts. The tariffs would cause the price of the vehicles to go up, which would dampen demand and slow auto sales, meaning fewer sales for the U.S. parts vendor, Robinet explains.

Additionally, automakers can’t just substitute a U.S.-made alternator for one made in Japan because parts are customized for particular vehicles.

Take all these developments together, and “there are still more unknowns than knowns when it comes to trade,” Robinet concludes. That makes it impossible to forecast how things will play out for U.S. manufacturers for the rest of 2019.

“If we can settle the tariff situation with China, that will remove one big barrier,” says Alexander. “But with the administration’s approach of one-by-one negotiations, other dominoes will have to fall for us to get real clarity.”

Tariffs are clearly creating economic uncertainty for large manufacturers, but how are they affecting smaller companies? Exports have contracted. According to the latest GBI (Gardner Business Index) that tracks smaller manufacturing activity, economic expansion is real at 53.4—but it’s not as robust as it had been a year ago. Note: February 2018 was the highest the index had ever seen—at a score of 60.

“Over the last six months, production has expanded at a relatively stable rate while supplier deliveries have experienced slowing growth since surging in mid-2018,” notes Michael Guckes, chief economist at Gardner Intelligence in a recent blog post. “This suggests that upstream suppliers are taking a careful approach to rebalancing supplies with current demand.”

The GBI diffuses six key indicators from monthly customer surveys from 50,000 durable goods and discrete manufacturing facilities. The index includes: new orders, production, backlog, employment, exports, and supplier deliveries.

In the metalworking industry, shops with 20 employees or less account for $1 billion to $1.5 billion in machine tools annually, according to Gardner Intelligence.