Best Drill Bits for Stainless Steel: Advice from Those Who Know It Best

Learn what makes austenitic and PH stainless steels so difficult to drill and how you can improve tool life and productivity.

Learn what makes austenitic and PH stainless steels so difficult to drill and how you can improve tool life and productivity.

Holemaking is the most common and often the most difficult of all metalworking operations. Nowhere is this truer than when working with austenitic (300-series) and precipitation-hardening (PH) stainless steels.

Work hardening, poor thermal conductivity and downright toughness—these are just a few of the failure mechanisms machinists might grapple with when drilling these challenging, though widely used, materials.

Read on to learn what makes stainless so problematic, and get advice on how to maximize tool life and productivity in holemaking operations.

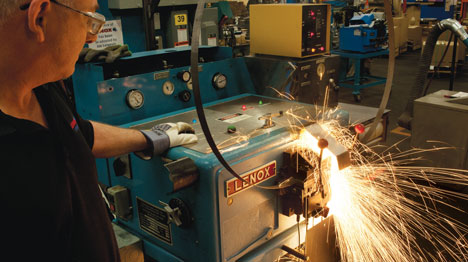

“Stainless steel is very heat sensitive,” says Alyssa O’Brien, a mechanical engineer with OSG. “Because of its chemical makeup, it doesn’t like to absorb or conduct heat. If the customer is spinning too fast, the heat stays localized right at the cutting edge,” O’Brien says. “Speed kills drills.”

Keith Hoover, a regional product manager at Kennametal, agrees. He explains that alloying elements like chromium and nickel increase corrosion resistance in stainless steels but also dramatically increase their tendency to work harden. “Those same elements make stainless much tougher to cut.”

One obstacle not yet mentioned is chip control. In contrast to austenitic grades, most 400-series stainless steels—whether martensitic or ferritic—produce relatively short, well-behaved chips. From a machining standpoint, they are closer to alloy steels such as 4140 or 8620 than to 300-series stainless steels.

Those with higher amounts of chromium, nickel and other alloying elements, as discussed in the previous section? Not so much. As many machinists are well aware, these metals generate long, stringy chips that are difficult to break and not only wrap around toolholders and spindles but also present a safety hazard.

For many years, the simplest solution has been peck drilling. Not a good idea, Hoover says. “Peck drilling generates a ton of heat at the point of cut, then you retract and let everything cool. When the drill reenters, it’s cutting into a freshly work-hardened surface. You repeat that cycle over and over, and tool life collapses.”

“When you don’t peck, there’s a good chance you can stay underneath that localized work-hardened zone, depending on feed rate, which can significantly improve tool life in stainless,” O’Brien adds.

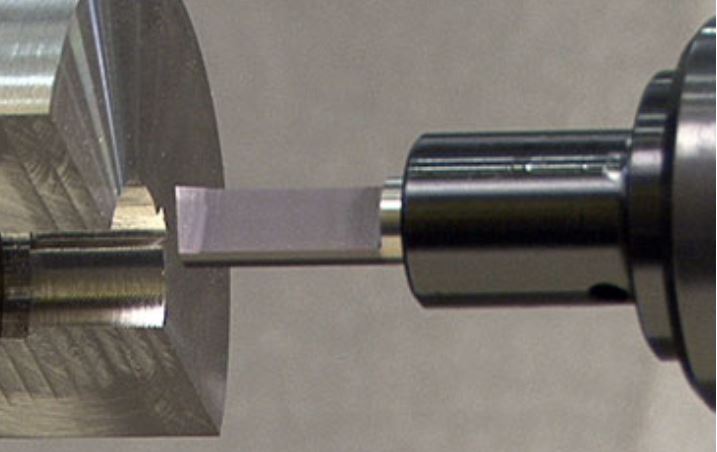

The current state of the art for these and similarly challenging drilling scenarios avoids all this: through-the-tool, high-pressure coolant (HPC) coupled with a high-quality carbide, modular or indexable drill bit mounted in an equally high-quality shrink-fit, hydraulic or mechanical toolholder. No pecking necessary.

But hold on. Maybe your shop has older equipment or a limited budget that places such niceties out of reach. Or given the abundance of high-mix, low-volume work these days, carbide with its higher price tag doesn’t make sense. You just want to make a few holes and move to the next job.

James Martinek, a sales development specialist responsible for category leadership with MSC Industrial Supply, suggests that carbide isn’t always the best choice. “If you want to drill stainless and are in a situation where you don’t want to use or can’t justify carbide, our recommendation is a vanadium high-speed steel (HSS). Otherwise, our guidance is pretty simple: A 140-degree solid carbide drill with an AlTiN coating is the best general recommendation for stainless steels, whether that’s 300-series, 400-series, or precipitation-hardening.”

Hoover seconds this, noting that when shops want productivity and accuracy, they move toward carbide. “The added stiffness improves hole accuracy and allows the tool to maintain hardness at the elevated temperatures you see in stainless,” he says. “In addition, carbide tools can take the heat far better than high speed, which starts to temper and lose hardness, but coated carbides maintain their wear resistance, which lets you run faster and be more productive.”

O’Brien qualifies this statement slightly. “If a shop is doing longer production runs and wants to maximize the use of a single tool, carbide usually delivers the best return on investment. There is a learning curve, but once shops get past that, carbide treats them well.”

Much of that learning curve comes down to using the correct cutting parameters. As a rule of thumb, assume that carbide runs a minimum of four times the surface speed of HSS. But with a coated tool, rigid setup and through-the-tool HPC, that multiplier can climb significantly higher, far beyond what a conventional jobber drill can sustain.

In either case, it’s essential to follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for the cutting tool and application. MSC Industrial Supply has a nationwide network of metalworking specialists available for consultation, just as OSG, Kennametal and practically all premium brands have human and digital resources for customer support. Don’t go it alone.

Hoover puts it bluntly: “A lot of shops slow down when they see problems, but that’s often the exact opposite of what they should do. What you really want to do is run that drill as hard and fast as it can physically take. That’s how you break the chip and avoid repeated engagement with a work-hardened surface.”

And as he and the others have noted, carbide can take the heat and the strain of cutting these tough stainless alloys at elevated parameters. This ensures that you leverage the tool’s full performance potential, while also justifying its higher cost. Doing so, however, requires the right speeds and feeds, as well as the setup just described.

Expanding on Martinek’s earlier statement, most of the cutting tool advancements over the last few years have been in coatings.

“The substrates were already excellent. It’s the coatings that are now driving the performance gains in stainless drilling. Looking at the industry as a whole, using anything other than a coated tool is pretty self-defeating,” he says. “So as I mentioned, AlTiN is the first recommendation for stainless, with TiAlN right behind it, depending on whether chipping or heat is the bigger issue.”

O’Brien and Hoover echo this, yet both suggest that geometry remains crucial to drill performance. Even with coatings doing much of the heavy lifting, features such as point angle, web thinning and flute design still play a critical role in controlling thrust, chip evacuation and heat at the cutting edge.

The main takeaways? Stay current on what the market has available, talk to your suppliers and, if appropriate, get out of your comfort zone.