As any experienced machinist or manufacturing engineer knows, accurate, efficient machining depends on the right workholding and toolholding. In turning, milling and grinding applications, that often means collets. Yet many newer operators lack a clear understanding of collet systems and their proper use.

The result? Misalignment and tool runout; poor cutter life and part quality; and reduced overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) as operators try to solve these problems.

What Is a Collet? Understanding Workholding Principles and Advantages Over Chucks

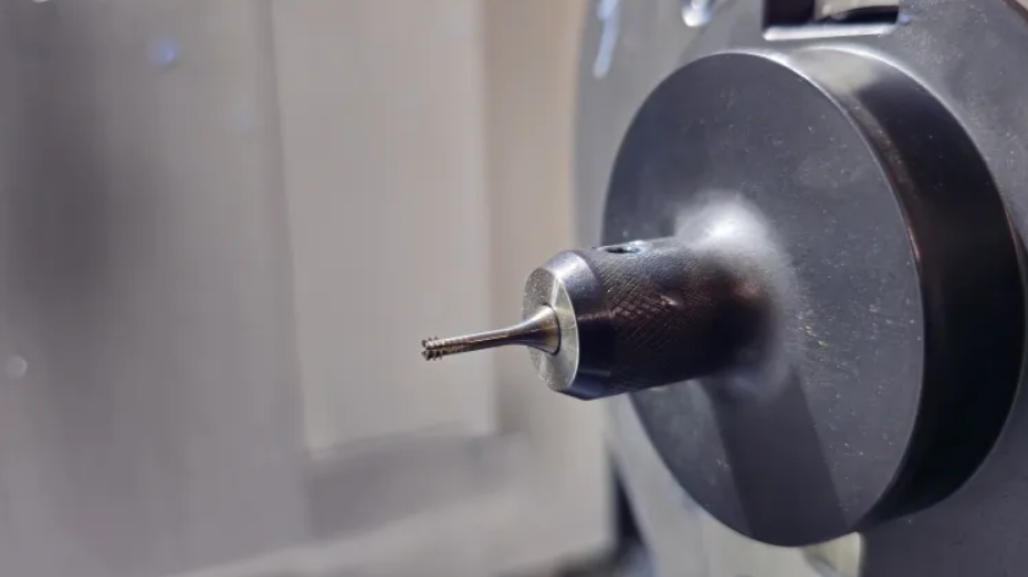

James Martinek, sales development and category leadership specialist at MSC Industrial Supply, explains that a collet is a slotted sleeve. It grips by collapsing uniformly around a tool shank or workpiece.

This collapse occurs when the collet is drawn into a matching taper or, in most toolholding systems, when a threaded nut forces the collet down into the taper. In either case, the clamping occurs uniformly, providing better concentricity than jaw-style chucks, which usually grip at only three points.

“Consider a knee mill, where the machinist loads a drill or end mill into the machine spindle,” Martinek says. “By tightening the drawbar, the collet is pulled up into the spindle taper—this squeezes down on the tool shank, securing it in place. In a lathe, by comparison, a collet is used to hold the workpiece rather than a cutting tool. This is what’s meant by workholding.”

Common Collet Types: ER, 5C, TG, R8, DA and Their Typical Applications

In this last example, the collet is most often a 5C or 16C, which can grip part diameters up to 1-1/16 inches and 1-5/8 inches, respectively. Both are standard for small-part workholding in turning and grinding applications. The less common 3J collet holds parts up to 1-1/4 inches. For gripping sawed blanks, a collet stop can be added to control length; otherwise collets are commonly applied in barfeeding applications.

Internal, or “step,” collets are another option. These are machined to size and used to grip a workpiece on a through-hole or counterbore. They do so without pulling the work axially, making them well-suited for secondary operations.

Similarly, dead-length systems such as those offered by Hainbuch, Forkardt Hardinge and other well-known tooling providers utilize an alternative mechanism that avoids the “pull back” seen with 5C and 16C collets. So-called emergency collets are available in nylon, brass and “soft” steel. Don’t let the name fool you, however, as shops routinely machine them for use in secondary operations and to grip irregularly shaped parts or raw material such as extrusions.

Each of the preceding examples describes workholding applications, but collets are also widely used for gripping cutting tools such as drills, reamers, taps and end mills, typically through a collet chuck. Common types:

ER collets are widely used, general-purpose toolholders. The largest, ER50, holds tool shanks up to 32 millimeters (1.26 inches) and has a nominal maximum of 34 millimeters.

TG collets (single-angle) are older and provide a strong grip but offer less flexibility than ER collets.

DA (double-angle) collets are less expensive and less common than the other two types. Their shorter, steeper taper also makes them less accurate than ER or TG collets.

“There are three main collet styles in the machining industry: ER, TG and double-angle,” Martinek explains. “Each requires its matching holder—ER chucks for ER, TG for TG and double-angle for double-angle.”

That might be it for the collet systems used in CNC machining centers and live tool-capable mill-turn lathes, but as Martinek alluded to earlier, there’s also the R8 collet interface found on Bridgeport-style milling machines, which many shops still rely on for prototypes, repair work and one-off operations.

These include MSC’s Vectrax-brand knee mill as well as those offered by Clausing, Sharp and numerous other clones of the original Bridgeport design, patented more than 60 years ago.

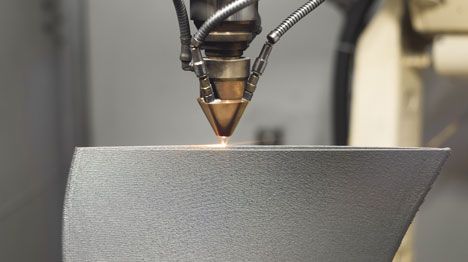

Toolholding Applications: Using Collets for Drills, End Mills and Reamers

Whatever the design, Martinek notes that it’s crucial to match the tool shank to the collet size—all have a limited collapse range and begin to lose accuracy as well as grip strength when you approach that limit. Check with the tooling manufacturer or a member of MSC Industrial Supply’s network of metalworking specialists for the technical details around your preferred toolholding system.

To that point, collets in general are the preferred choice for drilling, reaming, tapping and other holemaking operations because they provide good concentricity with quick changeover. ER systems in particular are common for toolholding because they cover a wide range of shank diameters with good accuracy.

In milling applications, try to limit the use of collet chucks to smaller cutters and finishing work. That’s because radial cutting forces can cause deflection or pullout; many shops use a 1/2" end mill diameter limit, based on material and cut depth. Also, minimize tool stick-out to improve stability and reduce pullout risk—never use a collet that’s “close enough.” As a rule of thumb, the collapse range is typically 0.02 inches (0.5 millimeters), depending on collet and tool diameter.

Maintenance and Care: Cleaning, Storage and Maximizing Collet Life

Collets are wear items that are subject to chips, coolant, vibration, radial forces and repeated tightening. To extend their usable lifespan, maintenance should be performed consistently and follow several best practices:

During setup and tool changes, thoroughly clean the collet and its mating seat. Chips and grit between these surfaces can cause damage and measurable runout, hurting precision. Remove debris with compressed air, then wipe surfaces with a clean cloth for best results. An ultrasonic cleaner is a timesaving investment here.

Once clean, inspect collets, nuts and seating areas for damage, including scoring, bell-mouthing, damaged slots or cracks in the collet. Replace any components that show signs of wear.

When installing cutting tools, tighten the collet nut just enough to securely hold the tool. Avoid using overtightening, since it can deform components and reduce collet life. Many tooling manufacturers offer torque wrenches for this purpose.

After use, store collets in a clean, dry place. Keep them separated with dividers or individual slots to avoid impact and damage from contact with other collets or tooling.

For long-term storage, apply a light layer of corrosion preventative after cleaning. This is especially important in high-humidity environments to prevent rust or oxidation.

Finally, know when not to use a collet. They are not ideal for parts with large diameter variations and irregular geometries, in heavy interrupted cuts or where aggressive axial force is present. In these situations, jaw-style chucks or dedicated workholding fixtures often provide a safer, more stable solution.

Used within their limits, collets remain one of the most efficient ways to hold cutting tools and parts during machining. The payoff is process consistency, better concentricity, quicker changeover and improved tool life.

Read more: The Real Cost of Collet Chucks